Authors

Dr Tom Frieden, President of Resolve to Save Lives. Former Director of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Commissioner of the New York City Health Department.

Dr Reena Gupta, Chief Medical Officer for Simple and Department of Medicine, University of California San Francisco.

Dr Andrew Moran, Director of Hypertension Control at Resolve to Save Lives, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York

Daniel Burka, Director of Product and Design at Resolve to Save Lives, Product for Simple.

Introduction

An estimated 1.4 billion people worldwide have high blood pressure and only 14% of people with hypertension worldwide have controlled blood pressure.1 Hypertension is the leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for 10.7 million deaths per year2 and the majority of those deaths are in low and middle-income countries. A strong public health program, backed with a well-designed digital information system for monitoring, has immense potential to save lives.

Large-scale hypertension programs in low-resource settings face many challenges. If a digital health system is to be successful, it must adapt to the practical challenges on the ground or it will never scale and data will be “garbage in, garbage out.” The volume of potential patients in a hypertension control program is overwhelming. In many countries, it’s common for hypertension to afflict one-in-five adults3 or more, and hypertension requires lifetime management. Managing huge patient populations over a long period of time can easily overwhelm both healthcare workers and data systems (especially paper-based systems). In many countries with understaffed public healthcare systems, clinical staff are already overworked: adding data needed to manage one fifth of the adult population is extraordinarily challenging.

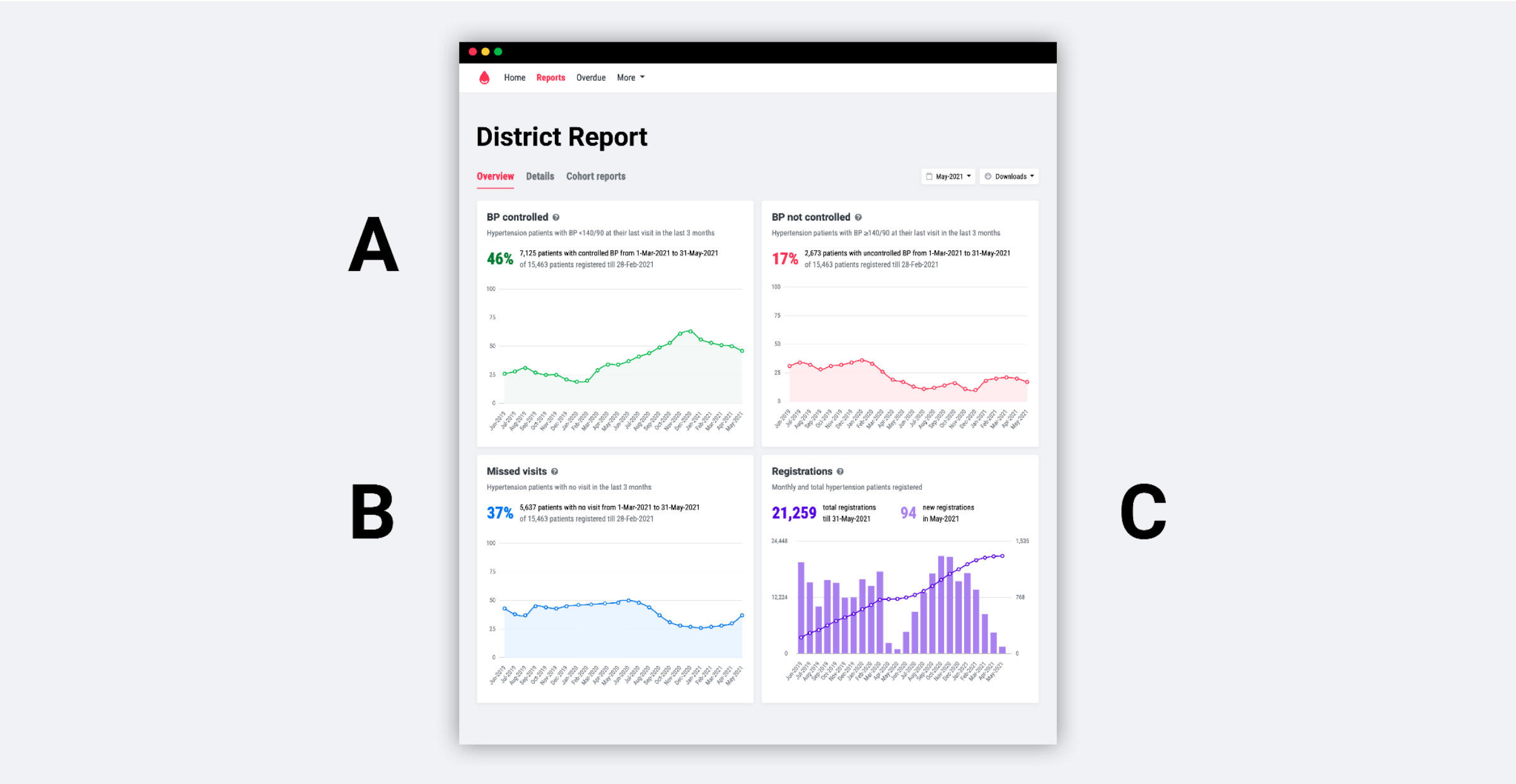

We think that a digital reporting system is fundamental to a successful hypertension control program at scale. As explained in the “S” of the WHO’s HEARTS technical package, a “system for monitoring” will drive feedback loops back into the system. Basic dashboards (data visualization with graphs) show where patients are being controlled and where hypertension control is weak and allow managers to strengthen the program.

To succeed at scale, a digital health system for managing a hypertension control program must focus ruthlessly on simplicity, speed, and scale. Making simple software sounds easy, but true simplicity requires saying “no” to many things that may seem necessary at first glance.

We have experience in developing and deploying software to manage NCDs. For the last 3.5 years we created Simple, a radically simple data collection and monitoring system for large-scale hypertension control programs. Simple has already scaled across India, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia. Today, Simple is used to manage over 1 million patients with hypertension and diabetes and is deployed in over 4500 active4 clinics. Simple is successful at scale because it doesn’t ask much of healthcare workers, is easy to learn, and provides real value to providers and program managers in tracking and improving performance.

Based on our experience, qualitative analysis, and successful uptake in thousands of public hospitals and clinics, we believe that a practical digital health information system in support of large-scale hypertension control or other chronic disease management program in low- and middle-income countries must follow these rules to succeed:

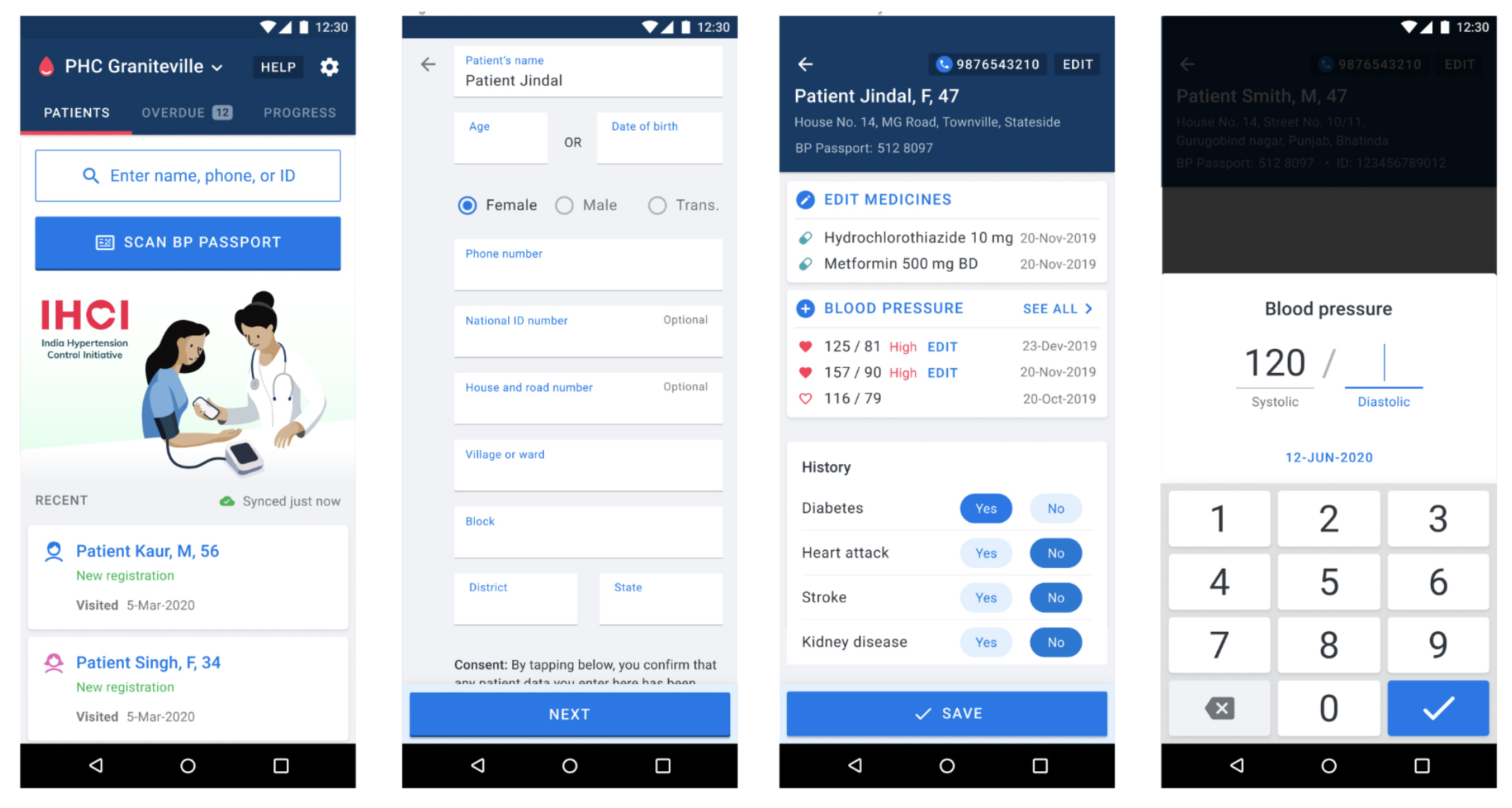

Rule 1 Very fast and easy-to-use

A health information system for hypertension and diabetes must be fast and easy-to-use. Clinicians in busy non-communicable disease (NCD) clinics in countries such as India will often see over 100 diagnosed hypertensive patients in a single day. Considering that patient encounters in many countries are squeezed into less than 4 minutes,5 it is crucial that data recording is under ~20 seconds for follow-up patients. This is possible, but requires radical simplicity and well-designed, modern software. A good system must also be very easy to use. Intuitive and simplified clinical software for hypertension management is:

- Easy to train: Ideally train users in situ at hospitals in <1 hour to reduce overhead for conducting trainings and to enable implementation scale.

- Easy to transfer knowledge: Staff turnover and task shifting are very common. If the digital tool is easy to learn, trained staff can teach new staff members to share the work.

We strongly encourage digital health developers to follow user-centered design principles to create digital tools that are easy-to-use by including healthcare workers directly in the design process and by building tools that fit into healthcare workers’ existing workflows or facilitating workflow redesign to more efficient patterns. From our observation, this user-centered process is frequently under-prioritized by officials residing in capital cities and by academics who design public health programs. We cannot overemphasize how critical a user-centered approach is to succeed in such a challenging, high volume, clinical environment.

Rule 2 Few key indicators

In order to make a fast and easy-to-use digital tool, it’s necessary to choose very few indicators for reporting. More indicators require more data entry and added complexity. And, more indicators dilute decision-makers’ attention from the top-line metrics that will make a hypertension control program successful.

Fundamentally, the indicators that we focus on are based on the WHO’s HEARTS technical package:

- Patients with BP controlled: This is the main metric for a hypertension control program because it focuses on the key outcome that saves lives: lower BPs. Indicator: How many enrolled patients have returned to care recently (in the last 3 months) with a BP measure <140/90 mmHg. [see definition]

- Patients who missed visits: How many patients are returning regularly (at least once every 3 months) for a BP measure or medications refill? This is critical because keeping chronic disease patients under care is both difficult and necessary to achieve BP control. We adjust this indicator for patients in long-term maintenance, receiving 6 months of medications. [see definition]

- Patients enrolled: Cumulative and monthly patient registrations into the hypertension management program. This is key because fewer than 50% of patients in most countries are aware that they have hypertension. Calculating the number of enrolled patients as a percentage of the total estimated hypertensive population in the region or a facility’s catchment area can be an added indicator.

Secondary indicators

- Drug stock of anti-hypertensive medications: Current stock of protocol anti-hypertensive medications, entered monthly. We also collect “stock received” each month, which allows for drug consumption reports. This is a key operational indicator, because inconsistent drug supply and stockouts are huge barriers in chronic disease treatment.

- Actions to recall patients to care: If your tool includes patient line lists or calling lists, recording how many patients were phoned by a healthcare worker is a good measure of health worker responsiveness and can be used for quality improvement. Keeping patients under care is crucial to a chronic disease program and many patients fall out of care without follow-up interventions.

Rule 3 Minimal data entry

With just a few indicators, choose the absolute bare minimum data elements that will improve patient care and report data up to improve the overall hypertension control program. The fewer data points that healthcare workers need to enter, the faster the system. Also, your data input quality will likely be higher with fewer inputs. It’s possible to run a program with these minimal data:

- Basic patient profile. We collect data primarily to identify patients and locate them for community follow-up: Name, sex, age, street address, village/neighborhood, district, state. We pre-fill district and state with the same locale as the registration facility to reduce data entry tasks for common fields.

- Mobile number. To call or automatically SMS/Whatsapp/message patients for critical follow-up tasks

- Unique ID. Where possible, we use a local health ID. We also created a UUID-based QR code identifier for places that don’t have a usable ID today.

- Key comorbidities. Used to prompt healthcare workers to conduct a basic cardiovascular disease history interview. Basic “yes/no” for history of heart attack, stroke, diabetes, or kidney disease.

- Blood pressures. Record all systolic and diastolic measurements over time. It is crucial to record follow-up visits reasonably consistently.

- Current medications. Many strong hypertension programs choose a simplified treatment protocol. A digital health system can collect each patient’s current medications. At each follow-up visit, a clinician can review the previous medications in order to treat the patient today to the treatment protocol. Medications data also gives health systems managers the ability to see which facilities are treating patients according to protocol and which are not.

- Follow-up data. Recording a patient’s next expected follow-up date and location (defaulting to the current facility) can aid in patient retention. Based on this data, overdue patient lists can be generated for automated follow-up (e.g. SMS or auto-phone calls), phone call lists, or for home follow-up by community health workers.

- Drug stock

Monthly data on end-of-month stock on hand in the facility pharmacy. Can also collect stock received during the month.

Data you may not need

We are frequently asked “Doesn’t a hypertension control app need to collect X?” A streamlined, user-friendly system that’s designed to be practical for busy healthcare workers inevitably excludes data that many people might deem necessary. For instance:

- Screened patient data. Most hypertension control programs emphasize screening patients. This generates big, impressive numbers, but these numbers overshadow and obscure the critical metrics of enrolled patients with controlled BP and estimated percentage of the population with controlled BP. Including screening data also means storing and processing at least 4 times as much patient data, including data for people with normal-range BP, versus only including diagnosed patients (e.g., making it harder to find patients in a search).

- Risk analysis data. Many systems collect BMI, cholesterol, and tobacco-use data in order to assess cardiovascular disease risk in each patient. This obviously has some use, but we think that the added complexity isn’t worth it. Almost all patients with high blood pressure are “high risk” — a clinician must help all patients living with hypertension to get to a controlled blood pressure.

- Clinical decision-support data. Like risk analysis, adding clinical decision support has benefits, but making confident treatment suggestions often requires an unrealistic amount of data entry. Balance what clinical algorithms can be trained versus what should be enforced with software.

- Lab data. Lab data (e.g. serum creatinine labs) are an obvious potential requirement in a hypertension program. Many low-resource settings that we see have poor access to laboratory testing in low-level health facilities. If we’re radically focused on simplicity, it’s possible to use a paper record for non-longitudinal data, such as labs.

Rule 4 Offline-first digital tool

We think it’s crucial to design software for data entry that is offline-first. Offline-first software can be used entirely offline and will synchronize data opportunistically when the user has sufficient internet. This approach is obvious in places with intermittent internet, but we suggest it even in urban locations or in locations with wifi.

A normal internet-enabled software application constantly has to check-in with a central server to transmit data. Each little transaction takes time and results in a slow-ish, inconsistent interface. With a good offline-first design, every tap on your app will be blazingly fast. It’s certainly extra work to develop using an offline-first approach, but the payoff is worth it.

Read more about our thoughts about offline-first in this blog post.

Other considerations

Patient retention measures

Keeping patients returning to care is one of the biggest challenges facing a chronic disease management program. Registering patients is relatively easy, but keeping them under care is hard — people have busy lives and many other concerns aside from their asymptomatic hypertension. So, creating tools for healthcare workers to reach out to patients is a good use of a digital information system.

Automated messages by SMS or WhatsApp are cheap and somewhat effective. Overdue patient calling lists are effective but require quite a bit of healthcare worker time. Line lists for follow-up by community healthcare workers are high effort but also very effective.

We do all of these things in Simple. Patient retention measures were the first ‘extra’ features that we added to the data recording tool. In Simple, we implemented:

- Automated SMS/Whatsapp reminders with personalized messages that remind patients to return to care: “Anand Singh, please return to PHC Riverside tomorrow for a BP measure and free medicines.”

- Patient line lists for overdue patients that can be used for calling patients or at-home follow-up by community health workers.

- In-app calling list so healthcare workers can call overdue patients.

Mobile devices

We think it’s important that an app should be adaptable to different types of devices. Some software is designed to the specifications of a specific tablet and large quantities of devices are purchased specifically to manage a health program. This can be a more stable environment for developers, but limits the scale of deployments possible in a large country. An app that is more device-agnostic can piggyback on devices already on-site for other programs (e.g. a tablet bought to support a local HIV program) or even on clinicians’ personal devices, if local laws permit it.

Interoperability

Is interoperability important? The unsatisfying answer: “it depends.” If you talk to tech people, interoperability is of paramount importance. While it’s important that data can be consolidated across multiple platforms, interoperability only becomes particularly useful when your system scales. Many tech teams overinvest in strict adherence to interoperability standards and underinvest in usability. Follow standards such as HL7 FHIR or whatever local standards exist, but don’t lose sight of the big picture.

Data ownership and hosting

Data ownership and hosting is a big deal and is very jurisdiction-dependent. Your digital health solution is going to manage patient records for a large population so it’s critical to take data ownership seriously. In our case, the local government (usually a Ministry of Health) owns their own data. Ensure that your system has clear and ethical data governance from an early stage and addresses this issue transparently at program initiation. Installation of a program may require temporary or periodical access to data systems by a technical team, and the ability to do this with appropriate approvals may be essential to program success.

Patient-focused apps

Giving patients control of their own data is a good idea. Empowering patients to monitor their own health and to nudge them towards control sounds promising too. There is limited evidence that apps for patients, by themselves, will measurably improve hypertension outcomes. We think that such apps show potential but we’re not confident that they will significantly improve patient health. That said, we created a BP Passport app that gives patients a wallet of their blood pressure and blood sugar readings and reminds them to take their daily medications — the jury is still out.

Conclusion

The primary goal of a successful digital health information system for a chronic disease program is to drive feedback loops into the program to improve the quality of care and actually improve patients’ health. Patients need feedback on their progress in lowering their blood pressure. Clinicians need a longitudinal record to monitor each patient’s progress and to treat them correctly. Decision-makers need key data insights that tell them where the hypertension control program is succeeding and where it’s struggling. A gold standard system can quickly indicate why patients have higher BPs in some hospitals and give feedback to officials to implement interventions to solve those problems.

To succeed, we suggest that you start with a very simple system and add complexity grudgingly. Simple tools are easier to use for healthcare workers, easier to comprehend for busy decision-makers, and will scale more easily. In the end, the best system is the one that helps the most patients to lower their blood pressures. Keep it simple.

Footnotes

- Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, Reed JE, Kearney PM, Reynolds K, et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation. 2016;134(6):441-50.

- Bloom DE, Cafiero ET, Jané-Llopis E, Abrahams-Gessel S, Bloom LR, Fathima S, et al. The Global Economic Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases. Geneva; 2011.

- Patricia M Kearney,et al. “Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data” in The Lancet. Volume 365, Issue 9455, 15 January 2005, Pages 217-223

- 4500 active clinics recorded >10 patients in Simple in the last week (Sept 25, 2021)

- Irving G, Neves AL, Dambha-Miller H, et al International variations in primary care physician consultation time: a systematic review of 67 countries. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017902. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017902